Places

"Met Lab"

(Metallurgical

Laboratory)

LOS ALAMOS AFTER THE WAR Places > LOS ALAMOS: THE LABORATORY

Places > LOS ALAMOS: THE LABORATORY

With the end of the Second World War, American policymakers anticipated that the Manhattan Project's infrastructure would be turned over to and managed by a largely civilian commission. General Leslie Groves initially thought this would happen soon after the ending of hostilities. His strategy for interim management of the complex was thus one of "hold the line," where he sought to maintain the essential soundness of the physical plant and the personnel that ran it, complete ongoing construction, and promote efficiency and economy. His most serious short-term problem was in retaining personnel, particularly at Los Alamos where many scientists and technicians were eager to return to civilian pursuits. In October 1945, J. Robert Oppenheimer resigned as director of the laboratory, and Groves selected Norris Bradbury, a scientist and Naval Reserve officer at Los Alamos, to replace him.

Bradbury's immediate responsibility was to keep the laboratory alive. Whether the lab would even remain at its present site had not been decided, but Groves felt that more and better bombs were needed and the lab should maintain the nucleus of its weapon staff. In a speech at the lab on October 1, Bradbury attempted to define the lab's postwar mission. Expressing hope that atomic weapons would never again be used and that developing weapons might end after a few years, he stated that to keep the nation's international bargaining position strong it was crucial for Los Alamos to continue to develop and stockpile weapons. Noting the need for more bomb tests, like the one at Trinity, he explained: Properly witnessed, properly publicized, further TR's (Trinity's) may convince people more than any manifesto that nuclear energy is safe only in the hands of a wholly cooperating world. It may also be pointed out that I believe that further TR's may be a goal which will provide some intellectual stimulus for people working here. Answers can be found; work is not stopped short of completion; and lacking the weapons aspect directly another TR might even be FUN. Bradbury proposed studies on the feasibility of the thermonuclear weapon—the Super—and a program on peacetime applications of nuclear energy. Morale and personnel loss nonetheless continued to be problems at Los Alamos, reaching its nadir in February 1946 when the water pipes froze solid for several weeks, with water having to be brought up from the Rio Grande in tank trucks and doled out in buckets. Groves, in response, upgraded living conditions at the site with major improvements in utilities, housing, and community facilities. He also sought to focus the laboratory more on weapons development by relocating various weapons production and assembly activities away from Los Alamos. Already at the close of the war, the engineering group of the laboratory's ordnance division began consolidating weapons assembly functions at Sandia Base on the old Albuquerque, New Mexico, airport. Groves now added a special Army battalion at Sandia to take charge of surveillance, field tests, and weapons assembly. In addition, he negotiated an agreement with Monsanto for the development and manufacture at its plant in Dayton, Ohio, of weapons components previously fabricated at Los Alamos.

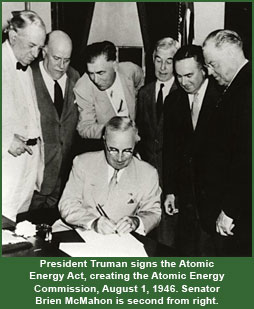

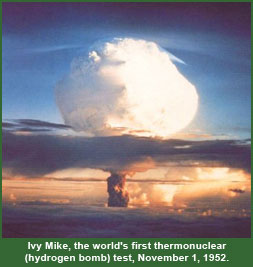

At the same time, the laboratory began preparations for a test of the effects of atomic weapons on naval vessels. The lab provided the technical direction and the atomic weapons for the two shot series, known as Operation Crossroads, which took place in July 1946 at Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands of the central Pacific. The following month, President Harry Truman signed the Atomic Energy Act, ensuring that nuclear weapons development, and hence Los Alamos itself, would be a civilian enterprise, not a military one. Civilians began to replace the military personnel that had been administering and providing security for the laboratory. The University of California agreed to continue to operate the site. In the years that followed, the emphasis at Los Alamos throughout the Cold War remained on nuclear weapons development, with Los Alamos scientists playing a critical role in the development of thermonuclear weapons. In 1953, the laboratory moved from its original location surrounding Ashley Pond to its present site at the other side of the canyon, and in 1957 the security gates came down and Los Alamos became an open city. Norris Bradbury's 25-year tenure as director came to an end in 1970, and in 1981 the name changed from Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory to Los Alamos National Laboratory.

|

The text for this page is original to the Department of Energy's Office of History and Heritage Resources. Portions were adapted or taken directly from Richard G. Hewlett and Oscar E. Anderson, Jr., The New World, 1939-1946: Volume I, A History of the United States Atomic Energy Commission (Washington: U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, 1972), 624-37; Lillian Hoddeson, et. al., Critical Assembly: A Technical History of Los Alamos during the Oppenheimer Years, 1943-1945 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 399-400, Bradbury quote on p. 400; Edith C. Truslow and Ralph Carlisle Smith, Manhattan District History: Project Y, The Los Alamos Project, Volume II, August 1945 through December 1946 (Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory, LAMS-2352 [Vol. II], 1961), 1-23. Also see Gregg Herken, Brotherhood of the Bomb: The Tangled Lives and Loyalties of Robert Oppenheimer, Ernest Lawrence, and Edward Teller (New York: Henry Holt, 2002) and Peter J. Westwick, The National Labs: Science in an American System, 1947-1974 (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000). The photograph of Bradbury, Oppenheimer, Feynman, Fermi, and others is courtesy Los Alamos National Laboratory. The identifications are from Richard G. Hewlett and Francis Duncan, Atomic Shield, 1947-1952: Volume II, A History of the United States Atomic Energy Commission (Washington: U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, 1972), opposite page 46. The photograph of President Harry Truman signing the Atomic Energy Act (including the close-up of Senator Brien McMahon) is courtesy the Department of Energy (DOE). The photograph of the "Ivy Mike" hydrogen bomb test is courtesy the Department of Energy's Nevada Site Office.