Processes

Uranium Mining, Milling, and Refining

BOMB TESTING AND WEAPON EFFECTS Processes

Processes

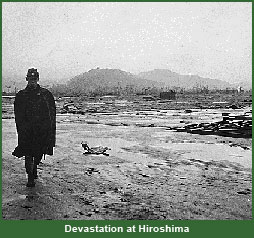

All of the work of the Manhattan Project culminated in two explosions over the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Uranium mining and refining, uranium isotope separation, plutonium production, and bomb design and development were steps on the way to the final outcome of wartime use. In 1943, when scientists at Los Alamos were only beginning to work out the physics and engineering of bomb design, preparations were already under way for a useable weapon that could be delivered by an airplane in combat. This involved choosing a suitable aircraft, building and testing bomb casings, training the flight crews for their missions, and developing a fuse to detonate the bomb at the right time. Prior to use, the plutonium bomb also was tested at the Alamogordo Bombing Range in the New Mexico desert on July 16, 1945. The test, named "Trinity," not only demonstrated that the complicated implosion device actually worked but also provided important information on the physical properties of a nuclear explosion, so as to design a delivery system that would allow for optimum weapon effects without unnecessarily endangering the pilot and crew of the delivery aircraft.

Assembly of both the uranium bomb and the plutonium bomb took place primarily at Los Alamos. The nearly completed bombs were shipped from the laboratory to the B-29 airfield at Tinian Island in the western Pacific Ocean. Final assembly took place at Tinian. A B-29 aircraft, the Enola Gay, delivered the Little Boy uranium bomb over Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. "Results clear cut, successful in all respects," radioed the Enola Gay to Tinian. Three days later, a second B-29 delivered the Fat Man plutonium bomb over Nagasaki. The crew reported that the flash was brighter, the shock waves greater, and the cloud was larger and moved up faster than at Hiroshima.

Nuclear explosions produce a yield, which is the amount of energy released measured in terms of the amount of conventional explosives that would release a similar amount of energy. They also have complex, if predictable, effects. When a mass of fissionable material goes critical, it undergoes an uncontrolled chain reaction and explodes. The immediate effect of the explosion is the unleashing of a tremendous quantity of energy in the form of blast, heat (or thermal radiation), and nuclear radiation. The explosion sends out a blast in the form of a shock wave and violent winds, accounting for half of the total energy output of the device. The blast is responsible for a significant fraction of bodily injury and destruction—knocking over buildings, bursting gas pipes, violently hurling debris and large objects. Qualitatively, these blast effects resemble those of conventional explosives, but the scale and the scope of the effects are much larger. In addition to the output of the initial blast, one third of the energy unleashed in the blast comes from heat in the form thermal radiation. High-energy radiation in the form of infrared, visible, ultraviolet light, and some x-ray light generates tremendous heat resulting in fires and severe burns. The fires can be so intense that they generate firestorms. The remaining energy from the explosion comes in the form of direct nuclear radiation. This form of energy releases high energy ionizing radiation mostly in the form of neutrons and gamma rays. Acute exposure to ionizing radiation can result in radiation sickness and severe biological damage.

In addition to these immediate effects of nuclear weapons, the long-term effects of radiation are among the most odious. While direct exposure to large quantities of nuclear radiation can cause immediate sickness and death, there are also long-term effects of smaller doses, such as increased incidence of cancer and genetic defects. A nuclear explosion generates radioactive debris, termed fallout, which can spread over a large area and can remain radioactive for a very long time. These radioactive particles can result in severe biological effects similar to direct exposure, but their potential for harm poses a threat over a much longer time period. To learn more about Bomb Testing and Weapon Effects, choose a web page from the menu below:

|

The text for this page is original to the Department of Energy's Office of History and Heritage Resources. The radio transmission from the Enola Gay is quoted in Vincent C. Jones, Manhattan: The Army and the Atomic Bomb, United States Army in World War II (Washington: Center of Military History, United States Army, 1988), 538; crew reports on Nagasaki bombing are from p. 541. Major sources consulted include Samuel Glasstone and Philip J. Dolan, eds., The Effects of Nuclear Weapons, 3rd ed. (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1977; prepared and published by the U.S. Department of Defense and the U.S. Department of Energy), and John F. Hogerton, ed., "Weapons Effects," The Atomic Energy Deskbook (New York: Reinhold Publishing Corporation, 1963; prepared under the auspices of the Division of Technical Information, U.S. Atomic Energy Commission), pages 600-604. See also the entry for "Weapons Phenomenology" in Hogerton, ed.; and the report on "The Atomic Bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki" in the official Manhattan District History, produced by the War Department in 1947 at the direction of Leslie Groves; this document is available in the University Publications of America microfilm collection, Manhattan Project: Official History and Documents (Washington: 1977), reel #1/12. The photograph of Paul Tibbets with his ground crew in front of the Enola Gay is reproduced from Jones, Manhattan: The Army and the Atomic Bomb, 535. The photograph of the Hiroshima mushroom cloud and the crater from the Indian test are courtesy of the Federation of American Scientists.