Places

"Met Lab"

(Metallurgical

Laboratory)

RICHLAND TOWN SITE: LIFE AT Hanford Places > Hanford Engineer Works

Places > Hanford Engineer Works

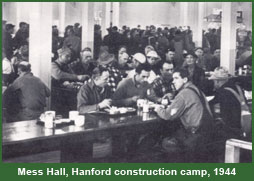

Due to the isolation of the Hanford site, Army and DuPont Corporation engineers planned for large on-site communities. The high-levels of radioactivity in the plutonium process meant that they could not follow the normal practice of having construction and plant-operating employees live adjacent to the production plants. Scientists had indicated that plant-operating employees could not safely reside within ten miles of the 100 and 200 area production facilities. Project engineers, in the interest of saving time, favored sites already occupied by rural villages, where they would be able to take advantage of existing grading, buildings, road networks, and utilities. After giving consideration to several options, the engineers agreed to establish two separate communities: a construction camp at the Hanford town site and an operating village at Richland. All private property at both sites was acquired by the federal government, and the local population evicted. Located in the far southeastern corner of the site about 25 miles from the main process areas, Richland in early 1943 had a population of 200 and was the center of an agricultural community of about 600 persons who derived their livelihood from farming the irrigated bottomlands near the junction of the Yakima and Columbia Rivers. Most of the commercial and civic structures of the village and some of the homes were built along the state highway that provided access eastward to the communities of Kennewick and Pasco and northward to Hanford and White Bluffs. The original buildings of Richland were of substantial construction, many of them cement or brick. Community services included an underground water system (but no central sewage system), electricity, and telephones. The roads were chiefly gravel or packed earth, but some had asphalt surfacing. Surrounding the village center were numerous small farms planted with orchards or other irrigated crops. Although Hanford camp had priority, planning and design of the construction and operating communities proceeded more or less simultaneously. Initial plans forecast a population of 6,500 for Richland, but after several recalculations eventually revised up to 17,500. Housing would consist of 2,500 conventional family units of relatively permanent construction and also 25 dormitories to house single men and women. DuPont originally planned for at least three-bedroom homes, but the Army, in the interest of the most economic use of project resources, insisted on two- or three-bedroom homes. To supplement this housing and expedite the development of the community, DuPont and the Army turned to portable prefabricated housing similar to that being built at the Oak Ridge site. A total of 1,800 units were ordered. Until January 1944, 80 percent of the Richland housing was occupied by construction personnel. By March, 50 percent was going to operating employees, 40 percent to construction, and 10 percent to government. As site construction wound down, the percentage of operating employees continued to rise. By late spring 1945, transformation of Richland into an industrial community of scientists, engineers, military administrators, and skilled workers and their collective families was nearly complete. In a fenced-in area at the center of the operating village were the wood-frame buildings of varying size that housed the HEW administrative headquarters. Immediately to the east and southeast of the headquarters and toward the low-lying Columbia River was "downtown" Richland, built around the original commercial center of the village. Here were stores and a variety of service facilities, a hotel for visitors, a theater, churches, a cafeteria, and the dormitories for single men and women. Surrounding downtown on the south, west, and northwest were residential areas, with neighborhood stores and service facilities. Most of the conventional houses were clustered in two large sections—one directly south of the village center, the other to the northwest—with here and there shade and fruit trees remaining from the farms that had occupied the area. On the outer fringes of the conventional housing sections were a few of the flat-roofed prefabricated houses, but most of these were concentrated in a roughly rectangular zone directly west of the administration buildings. As at Hanford camp, concessionaires operated most of the commercial facilities. Richland, as well, had no formal local government, with DuPont providing most normal community services—utilities, street maintenance, trash and garbage pickup, and fire and police protection. Population of Richland peaked at 15,401 in spring 1945, with a considerable drop during the summer resulting from completion of the last phases of construction and from a reduction in operating forces as operations were gradually stabilized. Wartime life at Richland was by no means easy. The War Department press release issued locally on August 6, 1945, doubtless overstated the situation when it described Richland as a "pleasant little town" filled with "pleasant Government-owned homes." Nonetheless, of the Manhattan Project's three operating communities, Richland most nearly resembled the typical American company town, owned and dominated by a great industrial concern. This was so partly because the Army's presence was not nearly as apparent as at Oak Ridge, with its Manhattan Engineer District headquarters, and numerous technical employees in uniform, nor as at Los Alamos, with its very substantial military population. Richland also had fewer outward signs of physical security, such as the high encircling fence patrolled by military police and dogs at the New Mexico site and the similar barriers erected at crucial points long the boundary of the Tennessee site. To the casual visitor, Richland appeared to be just one more wartime boomtown where the average employee and his or her family had to endure the usual minor hardships and inconveniences.

|

The text for this page is original to the Department of Energy's Office of History and Heritage Resources. Major sources consulted include the following. Richard G. Hewlett and Oscar E. Anderson, Jr., The New World, 1939-1946: Volume I, A History of the United States Atomic Energy Commission (Washington: U.S. Atomic Energy Commission, 1972), and Manhattan District History, Book IV - Pile Project, Volume 5 - Construction, and Volume 6 - Operation. Additional information about the region comes from Peter Bacon Hales, Atomic Spaces: Living on the Manhattan Project (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1997). The photograph of the mess hall is reproduced from the Department of Energy report Linking Legacies: Connecting the Cold War Nuclear Weapons Production Processes to their Environmental Consequences (Washington: Center for Environmental Management Information, Department of Energy, January 1997), 25.