People

RICHARD FEYNMAN (Physicist, Los Alamos Theoretical Division)

(Physicist, Los Alamos Theoretical Division)

People > Scientists

Richard Feynman has been described as "the best mind since Einstein." He was born on March 11, 1918, in New York City,

and did his undergraduate work at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Initially, he studied mathematics, but,

concerned about the abstraction and lack of application, briefly tried electrical engineering and then went into physics.

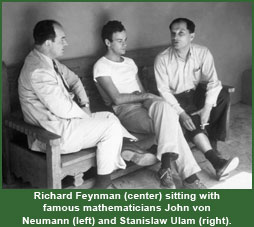

In 1939, he began graduate studies at Princeton University, studying under John Wheeler. He gave his first seminar at Princeton to

an audience that included Albert Einstein,

Wolfgang Pauli, and John von Neumann. The biographer James Gleick notes that at Princeton Feynman was

While at Princeton, Feynman was recruited in 1941 to work on uranium research leading to a possible atomic bomb. He later noted that his initial reaction was to decline since he was in the final stages of his thesis. But after returning to his thesis "for about three minutes," he "began to pace the floor and think about the thing. The Germans had Hitler and the possibility of developing an atomic bomb was obvious, and the possibility that they would develop it before we did was very much of a fright." Accepting the assignment, he began theoretical work on the separation of uranium-235. Wheeler, meanwhile, in early 1942 went to work on the bomb project at the Met Lab at the University of Chicago, and Feynman completed his Ph.D. in physics under the tutelage of Eugene Wigner. In early 1943, Edwin McMillan, assisting Robert Oppenheimer in setting up the weapons laboratory at Los Alamos, recruited Feynman for the effort. Feynman was one of the first to arrive. He was part of the Planning Board meeting of April 2 that dealt mostly with non-technical matters involving organizing the laboratory and community. He was assigned to Hans Bethe's Theoretical Division (T Division). Although Feynman was a junior physicist at the lab-"Los Alamos from below" was how he described his lowly status at a site populated by so many scientific giants--Bethe was impressed enough by the twenty-five year-old physicist to make him a group leader with four people working under him. Feynman's initial assignment involved calculations on uranium hydride, but over the next two years he would work on various aspects of bomb design and performance, including calculations relating to efficiency, critical mass, implosion, and neutron diffusion. Efficiency of the device was particularly difficult to calculate because it depended on the evolution of the assembly in time, but a breakthrough came early in the project. One evening following Robert Serber's overview of efficiency in his April 1943 introductory lectures, Bethe and Feynman discussed efficiency and "the physical parameters which matter" since they did not know how to solve the complicated diffusion and hydro-dynamical equations for supercritical systems. "I think we guessed," Bethe later recalled, that the rate of decrease of multiplication during the expansion, assuming known beginning and endpoints of the expansion, would be proportional to the relative expansion. To fix the overall constant, Bethe and Feynman used Serber's result, as described in his lectures, for small excesses over the critical mass, a case that was relatively simple to analyze. Using this approach, Bethe and Feynman developed a formula for efficiency. This, according to the authors of the technical history of Los Alamos, was "the most brilliant example of theoretical problem solving" under the difficult conditions at the lab. Bethe and Feynman identified the crucial physical parameters in the calculation. Guided by their extraordinary physical insight and understanding of physics, they were able to use their limited knowledge of the phenomena and available data to produce a workable approximate formula for efficiency. As this feat shows, finding the best approximations to theoretical problems hinged on a talent for integrating and interpreting information in relation to a deep understanding of the laws of physics, a skill possessed only by the most talented scientists. Brilliant scientist that he was, Feynman is almost as well known for his charisma and sense of humor. At Los Alamos, the lively and gregarious young physicist earned a reputation for arguing good-naturedly with Bethe. Their frequent arguments earned Feynman the moniker "the Mosquito" and Bethe "the Battleship." Yet, Feynman would later recall that he found war work dreadfully boring. His wartime diversions included shenanigans and practical jokes that would earn him a spot in Los Alamos lore. He enjoyed playing the bongo drums, cracking safes to secret filing cabinets for fun, and writing in code or slipping out of the gates just to toy with security personnel. Homesick, the displaced New York native reportedly hung a bagel above his bunk to admire.

After the war, Feynman left Los Alamos and, following Bethe who had returned to his academic post, accepted a position at Cornell University in Ithaca, New York. Unlike Bethe, Feynman did not play a significant role in the post-war development of either the military or peaceful atom. In 1950, he accepted a position at the California Institute of Technology where he would remain for the rest of his career. In 1965, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in physics for his "fundamental work in quantum electrodynamics, with deep-ploughing consequences for the physics of elementary particles." In 1986, he was a member of the committee that investigated the explosion of the space shuttle Challenger. Feynman died on February 15, 1988, in Pasadena, California. Feynman was arguably the best theoretical physicist the United States has produced. The physicist Freeman Dyson, a colleague of Feynman's in their groundbreaking work on quantum electrodynamics, described him as "half genius and half buffoon," an estimation later revised into, "all genius and all buffoon."

|

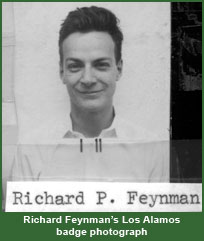

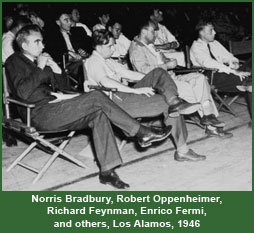

The text for this page is original to the Department of Energy's Office of History and Heritage Resources. Major sources consulted include the following. Lillian Hoddeson, et. al. Critical Assembly: A Technical History of Los Alamos during the Oppenheimer Years, 1943-1945 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 68, 84, 157-60, 178-79, 181, 183, 246, 307, 331-32, 355, 408-9, 417, "I think we guessed" quote, p. 183, "the most brilliant example" quote, pp. 408-9; Richard P. Feynman, Surely You're Joking, Mr. Feynman!: Adventures of a Curious Character (New York: W.W. Norton and Company, 1985), 99-164, "for about three minutes" quote, p. 100, "Los Alamos from below," p. 107. page 100. "the best mind since Einstein" is the title of a documentary on Feynman, a Nova production for BBC-TV in association with WGBH/Boston, first aired 1993. James Gleick, Genius: The Life and Science of Richard Feynman (New York: Pantheon Books, 1992), quote p. 134. A short biography of Feynman and his Nobel lecture is at http://nobelprize.org/nobel_prizes/physics/laureates/1965/feynman-bio.html. For a brief biography, see also http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/Biographies/Feynman.html. For a book-length biography, see Jagdish Mehra, The Beat of a Different Drum: the Life and Science of Richard Feynman (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), Freeman Dyson quote, p. xxi.. An important study of Feynman's scientific contributions is, Silvan S. Schweber, QED and the Men Who Made It (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994). Feynman's playful relationship with Hans Bethe comes from Kai Bird and Martin J. Sherwin's book, American Prometheus: the Triumph and Tragedy of J. Robert Oppenheimer (New York: A.A. Knopf, 2005), p. 217. In The Physicists: The History of a Scientific Community in Modern America (Harvard: Harvard University Press, 2005), Daniel J. Kevles describes Feynman's wartime antics, including the tale of the bagel, p. 330. Feynman's badge photograph and the picture of him chatting with John von Neumann and Stanislaw Ulam appear courtesy of Los Alamos National Laboratory. The image of Los Alamos scientists attending an August 1946 colloquium is also courtesy Los Alamos National Laboratory. Accompanying Feynman in the audience are, left to right, first row: Norris E. Bradbury, John H. Manley, Enrico Fermi, J. M. B. Kellogg. Second row: Robert Oppenheimer, Richard P. Feynman, Phil B. Porter. Third row: Gregory Breit (partially hidden), Arthur Hemmendinger, and Arthur D. Schelberg.