|

JAPAN SURRENDERS JAPAN SURRENDERS

(August 10-15, 1945)

Events

>

Dawn of the Atomic Era, 1945

-

The War Enters Its Final Phase, 1945

-

Debate Over How to Use the Bomb, Late Spring

1945

-

The Trinity Test, July 16, 1945

-

Safety and the Trinity Test, July 1945

-

Evaluations of Trinity, July 1945

-

Potsdam and the Final Decision to Bomb, July

1945

-

The Atomic Bombing of Hiroshima, August 6,

1945

-

The Atomic Bombing of Nagasaki, August 9,

1945

-

Japan Surrenders, August 10-15, 1945

-

The Manhattan Project and the Second World War,

1939-1945

Prior to the atomic attacks on

Hiroshima and

Nagasaki, elements existed within the Japanese government that

were trying to find a way to end the war. In June

and July 1945, Japan attempted to enlist the help of the

Soviet Union to serve as an intermediary in

negotiations. No direct communication occurred with

the United States about peace talks, but American leaders

knew of these maneuvers because the United States for a

long time had been intercepting and decoding many internal

Japanese diplomatic communications. From these

intercepts, the United States learned that some within the

Japanese government advocated outright surrender. A

few diplomats overseas cabled home to urge just

that.

From the replies these diplomats received from Tokyo, the

United States learned that anything Japan might agree to

would not be a surrender so much as a "negotiated peace"

involving numerous conditions. These conditions

probably would require, at a minimum, that the Japanese

home islands remain unoccupied by foreign forces and even

allow Japan to retain some of its wartime conquests in

East Asia. Many within the Japanese government were

extremely reluctant to discuss any concessions, which

would mean that a "negotiated peace" to them would only

amount to little more than a truce where the Allies agreed

to stop attacking Japan. After twelve years of

Japanese military aggression against China and over three

and one-half years of war with the United States (begun

with the surprise attack on Pearl Harbor), American

leaders were reluctant to accept anything less than a

complete Japanese surrender.

The one possible exception to this was the personal

status of the emperor himself. Although the Allies

had long been publicly demanding "unconditional

surrender," in private there had been some discussion of

exempting the emperor from war trials and allowing him to

remain as ceremonial head of state. In the end, at

Potsdam, the Allies (right) went with both a "carrot and a

stick," trying to encourage those in Tokyo who advocated

peace with assurances that Japan eventually would be

allowed to form its own government, while combining these

assurances with vague warnings of "prompt and utter

destruction" if Japan did not surrender immediately.

No explicit mention was made of the emperor possibly

remaining as ceremonial head of state. Japan

publicly rejected the Potsdam Declaration, and on July 25,

1945, President Harry S. Truman gave

the order to commence atomic attacks

on Japan as soon as possible. The one possible exception to this was the personal

status of the emperor himself. Although the Allies

had long been publicly demanding "unconditional

surrender," in private there had been some discussion of

exempting the emperor from war trials and allowing him to

remain as ceremonial head of state. In the end, at

Potsdam, the Allies (right) went with both a "carrot and a

stick," trying to encourage those in Tokyo who advocated

peace with assurances that Japan eventually would be

allowed to form its own government, while combining these

assurances with vague warnings of "prompt and utter

destruction" if Japan did not surrender immediately.

No explicit mention was made of the emperor possibly

remaining as ceremonial head of state. Japan

publicly rejected the Potsdam Declaration, and on July 25,

1945, President Harry S. Truman gave

the order to commence atomic attacks

on Japan as soon as possible.

Following the bombing of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945

(left), the Japanese government met to consider what to do

next. The emperor had been urging since June that

Japan find some way to end the war, but the Japanese

Minister of War and the heads of both the Army and the

Navy held to their position that Japan should wait and see

if arbitration via the Soviet Union might still produce

something less than a surrender. Military leaders

also hoped that if they could hold out until the ground

invasion of Japan began, they would be able to inflict so

many casualties on the Allies that Japan still might win

some sort of negotiated settlement. Next came the

virtually simultaneous arrival of news of the Soviet

declaration of war on Japan of August 8, 1945, and the

atomic bombing of Nagasaki of the following day.

Another Imperial Council was held the night of August

9-10, and this time the vote on surrender was a tie,

3-to-3. For the first time in a generation, the

emperor (right) stepped forward from his normally

ceremonial-only role and personally broke the tie,

ordering Japan to surrender. On August 10, 1945,

Japan offered to surrender to the Allies, the only

condition being that the emperor be allowed to remain the

nominal head of state. Following the bombing of Hiroshima on August 6, 1945

(left), the Japanese government met to consider what to do

next. The emperor had been urging since June that

Japan find some way to end the war, but the Japanese

Minister of War and the heads of both the Army and the

Navy held to their position that Japan should wait and see

if arbitration via the Soviet Union might still produce

something less than a surrender. Military leaders

also hoped that if they could hold out until the ground

invasion of Japan began, they would be able to inflict so

many casualties on the Allies that Japan still might win

some sort of negotiated settlement. Next came the

virtually simultaneous arrival of news of the Soviet

declaration of war on Japan of August 8, 1945, and the

atomic bombing of Nagasaki of the following day.

Another Imperial Council was held the night of August

9-10, and this time the vote on surrender was a tie,

3-to-3. For the first time in a generation, the

emperor (right) stepped forward from his normally

ceremonial-only role and personally broke the tie,

ordering Japan to surrender. On August 10, 1945,

Japan offered to surrender to the Allies, the only

condition being that the emperor be allowed to remain the

nominal head of state.

Planning for the use of additional nuclear weapons

continued even as these deliberations were ongoing.

On August 10, Leslie Groves reported to

the War Department that the next bomb, another

plutonium implosion weapon, would be

"ready for delivery on the first suitable weather after 17

or 18 August." Following the destruction of

Hiroshima and Nagasaki, only two targets remained from the

original list: Kokura Arsenal and the city of

Niigata. Groves therefore requested that additional

targets be added to the target list. His deputy,

General Kenneth Nichols, suggested

Tokyo. Truman, however, ordered an immediate

halt to atomic attacks while surrender negotiations were

ongoing. As the Secretary of Commerce Henry Wallace

recorded in his diary, Truman remarked that he did not

like the idea of killing "all those kids." Planning for the use of additional nuclear weapons

continued even as these deliberations were ongoing.

On August 10, Leslie Groves reported to

the War Department that the next bomb, another

plutonium implosion weapon, would be

"ready for delivery on the first suitable weather after 17

or 18 August." Following the destruction of

Hiroshima and Nagasaki, only two targets remained from the

original list: Kokura Arsenal and the city of

Niigata. Groves therefore requested that additional

targets be added to the target list. His deputy,

General Kenneth Nichols, suggested

Tokyo. Truman, however, ordered an immediate

halt to atomic attacks while surrender negotiations were

ongoing. As the Secretary of Commerce Henry Wallace

recorded in his diary, Truman remarked that he did not

like the idea of killing "all those kids."

On August 12, the United States announced that it would

accept the Japanese surrender, making clear in its

statement that the emperor could remain in a purely

ceremonial capacity only. Debate raged within the

Japanese government over whether to accept the American

terms or fight on. Meanwhile, American leaders were

growing impatient, and on August 13 conventional air raids

resumed on Japan. Thousands more Japanese civilians

died while their leaders delayed. The Japanese

people learned of the surrender negotiations for the first

time when, on August 14, B-29s showered Tokyo with

thousands of leaflets containing translated copies of the

American reply of August 12. Later that day, the

emperor called another meeting of his cabinet and

instructed them to accept the Allied terms immediately,

explaining "I cannot endure the thought of letting my

people suffer any longer"; if the war did not end "the

whole nation would be reduced to ashes." On August 12, the United States announced that it would

accept the Japanese surrender, making clear in its

statement that the emperor could remain in a purely

ceremonial capacity only. Debate raged within the

Japanese government over whether to accept the American

terms or fight on. Meanwhile, American leaders were

growing impatient, and on August 13 conventional air raids

resumed on Japan. Thousands more Japanese civilians

died while their leaders delayed. The Japanese

people learned of the surrender negotiations for the first

time when, on August 14, B-29s showered Tokyo with

thousands of leaflets containing translated copies of the

American reply of August 12. Later that day, the

emperor called another meeting of his cabinet and

instructed them to accept the Allied terms immediately,

explaining "I cannot endure the thought of letting my

people suffer any longer"; if the war did not end "the

whole nation would be reduced to ashes."

The only question remaining now was if Japan's military

leaders would allow the emperor to surrender.

Loyalty to the emperor was an absolute in the Japanese

military, but so was the refusal to surrender, and now

that the two had come into conflict, open rebellion was a

possible result. The emperor recorded a message in

which he personally accepted the Allied surrender terms,

to be broadcast over Japanese radio the following

day. This way everyone in Japan would know that

surrender was the emperor's personal will. Some

within the Japanese military actually attempted to steal

this recording before it could be The only question remaining now was if Japan's military

leaders would allow the emperor to surrender.

Loyalty to the emperor was an absolute in the Japanese

military, but so was the refusal to surrender, and now

that the two had come into conflict, open rebellion was a

possible result. The emperor recorded a message in

which he personally accepted the Allied surrender terms,

to be broadcast over Japanese radio the following

day. This way everyone in Japan would know that

surrender was the emperor's personal will. Some

within the Japanese military actually attempted to steal

this recording before it could be broadcast, while others attempted a more general military

coup in order to seize power and continue the war.

Other elements of the Japanese military remained loyal to

the emperor. The Minister of War, General Anami

Korechika, personally supported continuing the war, but he

also could not bring himself to openly rebel against his

emperor. The strength of his dilemma was such that

he opted for suicide as the only honorable way out.

In the end, his refusal to assist the coup plotters was

instrumental in their defeat by elements within the

military that remained loyal to the emperor.

broadcast, while others attempted a more general military

coup in order to seize power and continue the war.

Other elements of the Japanese military remained loyal to

the emperor. The Minister of War, General Anami

Korechika, personally supported continuing the war, but he

also could not bring himself to openly rebel against his

emperor. The strength of his dilemma was such that

he opted for suicide as the only honorable way out.

In the end, his refusal to assist the coup plotters was

instrumental in their defeat by elements within the

military that remained loyal to the emperor.

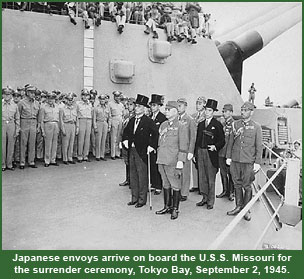

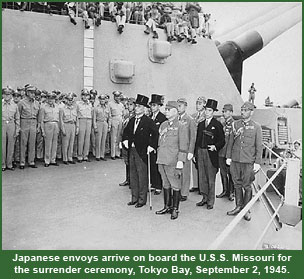

On August 15, 1945, the emperor's broadcast announcing

Japan's surrender was heard via radio all over

Japan. For most of his subjects, it was the first

time that they had ever heard his voice. The emperor

explained that "the war situation has developed not

necessarily to Japan's advantage," and that "the enemy has

begun to employ a new and most cruel bomb." Over the

next few weeks, Japan and the United States worked out the

details of the surrender, and on September 2, 1945, the

formal surrender ceremony took place on the deck of the

U.S.S. Missouri. On August 15, 1945, the emperor's broadcast announcing

Japan's surrender was heard via radio all over

Japan. For most of his subjects, it was the first

time that they had ever heard his voice. The emperor

explained that "the war situation has developed not

necessarily to Japan's advantage," and that "the enemy has

begun to employ a new and most cruel bomb." Over the

next few weeks, Japan and the United States worked out the

details of the surrender, and on September 2, 1945, the

formal surrender ceremony took place on the deck of the

U.S.S. Missouri.

-

The War Enters Its Final Phase, 1945

-

Debate Over How to Use the Bomb, Late Spring

1945

-

The Trinity Test, July 16, 1945

-

Safety and the Trinity Test, July 1945

-

Evaluations of Trinity, July 1945

-

Potsdam and the Final Decision to Bomb, July

1945

-

The Atomic Bombing of Hiroshima, August 6,

1945

-

The Atomic Bombing of Nagasaki, August 9,

1945

-

Japan Surrenders, August 10-15, 1945

-

The Manhattan Project and the Second World War,

1939-1945

Previous  Next Next

Sources and notes for this page.

The text for this page is original to the Department of

Energy's

Office of History and Heritage Resources. The surrender negotiations are detailed in

Gerhard L. Weinberg,

A World at Arms: A Global History of World War II

(New York: Cambridge University Press, 1994),

886-893. On the availability of the next plutonium

bomb by August 17 or 18, see the memorandum,

Leslie Groves to George Marshall,

August 10, 1945, which is in Groves's file of "Top

Secret" MED Correspondence, 1942-1946 (available from

the

National Archives (NARA)

on microfilm M1109). For Groves's request for

additional targets and Kenneth Nichols's suggestion that

Tokyo be added to the target list, see Groves to General

Henry "Hap" Arnold, August 10, 1945, which is also in

Groves's "Top Secret" MED correspondence. The

photographs of the U.S.S. Missouri during the

surrender ceremony and of the B-29s are courtesy

NARA. The photograph of the

Potsdam conference

is courtesy the

Truman Presidential Library. The photograph of the mushroom cloud over

Hiroshima

is courtesy the

United States Air Force (USAF)

(via NARA). The portrait of Emperor Hirohito is

courtesy the United States Army Signal Corps (via the

Library of Congress (LOC)). The photograph of Fat Man is courtesy the U.S.

Army Corps of Engineers (via NARA). The photograph

of the Japanese soldiers on Guam is courtesy the

LOC.

Home |

History Office

|

OpenNet

|

DOE

|

Privacy and Security Notices

About this Site

|

How to Navigate this Site

|

Note on Sources

|

Site Map |

Contact Us

|